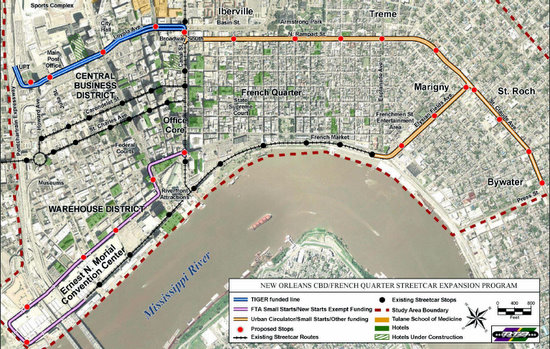

Map of the three phases of the streetcar expansion (via NORTA.com)

Streetcars are an iconic fixture in New Orleans, a reflection of our city’s connection to the past. Although the technology is old and often inefficient, we cling to these aging steel transports because of their beauty, craftsmanship and history.

The nexus of all of this is the St. Charles streetcar line, which has run through Uptown and the CBD since the early 19th Century. We take pride in the fact that it is the oldest continually operating streetcar line in the nation.

Today, there are plans to extend streetcar lines to other parts of the city, capitalizing off of the perceived success of the much newer Canal Street line. Instead of just a quaint remembrance largely for tourists, these plans aim to turn streetcars into a primary mode of transportation for all New Orleanians.

Already plans are in motion to construct a spur to go between the Union Passenger Termination and Canal Street which would almost (but not quite) create another connection between the St. Charles Streetcar Line and the Canal Line. Another plan will sent a streetcar line down through the Marigny and the Bywater.

Owen Courrèges

Now, I don’t believe these plans are necessarily misguided, but I do wonder if new streetcar lines are actually going through a proper cost-benefit analysis. The purpose of our public transportation should be to transport the most people to the most places in the least time for the least money. The name of the game is overall ridership – not just of a single line, but of the entire public transit system.

Throughout the country, other cities have been building light rail systems that have largely not improved overall ridership, and have actually made some trips inconvenient. In Houston, for example, the construction of a seven-mile light rail line into downtown entailed shutting down multiple parallel bus lines, including a free “trolley” line. The ridership numbers on the rail line were satisfactory, but only because the system was reoriented towards insuring high ridership numbers for a single transit line.

Transit rail infrastructure is thus a problem when it becomes an end unto itself. The purpose should not be to have more rail, but to provide cost-effective public transport. Because of its vastly higher capital costs (combined with comparable operating costs), rail transit will rarely win a cost-benefit analysis versus buses. Also, buses are more flexible because they aren’t tied down to a single rail line, providing smoother operation.

Ultimately, the main reason why streetcars began to disappear in the 1920’s and 30’s is because they are an older, more expensive technology. Their time had passed.

Of course, part of the problem is how we define “cost-effective.” The low-hanging fruit for public transit (i.e., those riders who are easiest to entice) are those with limited transportation options, usually poorer individuals without cars. Rail advocates often point out that while buses may appear more cost-effective, they do not attract “choice” riders, i.e. those who would not normally use buses.

Let’s call this what it really is. “Choice” riders are people who are too snobby to ride the bus but will ride on rail transit because they perceive it as being more upper-class. It should be self-evident that we should not be spending copious amounts of scarce funds to encourage the wealthy and middle class to use public transit.

On the other hand, New Orleans is a special case. Our city thrives on its image, which not only feeds tourism but is also cherished by residents. Streetcars are a part of that image, and it does actually tie into the bottom line. Moreover, streetcars are actually much cheaper to construct than modern light rail systems and tend to interfere less with traffic.

To conclude, then, it is not necessarily the case that proposed streetcar expansions are a bad idea. In particular cases, they may indeed be a better choice than existing bus lines. Heck, New Orleans may even benefit from a small streetcar network, as is planned. However, on a grand scale the age of the streetcar is simply gone. Nostalgia is simply not a good transit policy, no matter how much we may wish it to be.

Owen Courrèges, a New Orleans attorney and resident of the Garden District, offers his opinions for UptownMessenger.com on Mondays. He has previously written for the Reason Public Policy Foundation.

Buses use roads. Are roads free? Are their costs exogenous?

Rail infrastructure is more permanent than bus infrastructure. Which is more likely to attract adjacent development, especially with transit-oriented zoning? A bus stop, or a rail station? Maybe you should ask Domain Companies, who are making a huge investment along the future Loyola streetcar line.

The ultimate reason that streetcars disappeared is that the federal government decided to subsidize auto infrastructure and development over all other modes. You get what you pay for.

You say that “the purpose of our public transportation should be to transport the most people to the most places in the least time for the least money.” That’s nice, but there are other worthy objectives for public transportation, and some of them are federally mandated, such as providing equal access to transit for people in poor and minority neighborhoods.

allie,

Buses use roads. Are roads free? Are their costs exogenous?

Roads aren’t free, but we need them irrespectively. Ambulance, fire, ground-level freight and personal autos all need roads. Moreover, when it comes to freeways, the vast amount of capital and maintenance costs are paid for by gasoline taxes and other fees placed on motorists. Fairbox recovery doesn’t begin to pay the capital costs of rail (at least in most cases).

Rail infrastructure is more permanent than bus infrastructure. Which is more likely to attract adjacent development, especially with transit-oriented zoning?

There are multiple problems with this argument. First of all, attracting adjacent development isn’t a big deal if all you’re doing is reorienting development, particularly in an area that already has a high population density. Secondly, in many cases “transit-oriented development” has been pushed artificially with government subsidies and manipulation of land-use controls (see Portland, for example).

Thirdly, and perhaps most importantly, this misses the flipside. What if the anticipated development doesn’t occur? What if the neighborhood changes and ridership isn’t there? Bus lines can be easily moved to suit ridership, while rail is absolutely fixed — if you plan wrong or just predict wrong, it’s a monumental waste of resources. That’s part of what I meant when I said buses are more flexible. Buses can change to suit a changing city, rail cannot.

You say that “the purpose of our public transportation should be to transport the most people to the most places in the least time for the least money.” That’s nice, but there are other worthy objectives for public transportation, and some of them are federally mandated, such as providing equal access to transit for people in poor and minority neighborhoods.

As the objectives of public transit stray further from simply getting people from point A to point B to manipulating development, they get more questionable (I understand the equal access mandate as well, although it’s arguably unnecessary today).

No, freeways do not pay for themselves. The gas tax has steadily eroded in value and the highway trust fund requires “replenishing” every six years at minimum. A gas tax is not a user fee. At best, it attempts to capture the externalities of carbon use, but it fails at this by being not nearly expensive enough.

Also, your argument that personal autos need roads is exactly my point. Why should the production, ownership, and maintenance of personal automobiles be subsidized at a greater amount than public transportation? Why are the costs of transportation passed on to individuals through building roads that necessitate car ownership? These are choices we as a society make. Our roads and car culture did not appear sui generis; they are a result of specific policy initiatives over the past hundred years.

The equal access mandate is not “arguably unneccessary.” Many people don’t own vehicles, especially in New Orleans. These people need access to employment. They need to be able to buy groceries, since there is probably no place to buy fresh fruits and vegetables within walking distance of their residence. They need to be able to visit friends and family and conduct their lives. Until we build neighborhoods that have abundant amenities within walking distance (oh hey, zoning!), you can’t expect that everyone should spend x% of their monthly budget on the enormous expense of private car ownership.

alli,

No, freeways do not pay for themselves. The gas tax has steadily eroded in value and the highway trust fund requires “replenishing” every six years at minimum. A gas tax is not a user fee. At best, it attempts to capture the externalities of carbon use[.]

As I recall, the gas tax captures over 80% of freeway costs. Also, the gas tax is not and has never been designed to capture the externalities of gasoline usage. The gas tax predates the modern debate over these externalities, which are extremely hard to value. Besides, those tax dollars don’t go to mitigating these (often debatable) externalities and never have.

This also negates your argument that personal autos are being “subsidized” to such a large extent. Even granting that the gasoline tax should be high enough to cover 100% of freeway construction costs, the difference with public transit is still that it is massively subsidized by taxes not universally paid by transit users. Auto users pay gas taxes and tolls, while transit users pay fares. An apples-to-apples comparison requires that you weight these accordingly.

The equal access mandate is not “arguably unneccessary.” Many people don’t own vehicles, especially in New Orleans. These people need access to employment. They need to be able to buy groceries, since there is probably no place to buy fresh fruits and vegetables within walking distance of their residence. They need to be able to visit friends and family and conduct their lives. Until we build neighborhoods that have abundant amenities within walking distance (oh hey, zoning!), you can’t expect that everyone should spend x% of their monthly budget on the enormous expense of private car ownership.

I actually agree with you here that this is good public policy for transit to primarily serve the poor. As my column argued, we need to be picking at the “low-hanging fruit,” i.e., poor persons without cars, not going after the wealthy and middle class who can afford personal automobiles. The drive to build more rail comes at the expense of bus networks that serve the poor.

Just look at Los Angeles — the NAACP actually sued the city because it was building light rail and subways in rich areas while cutting bus service to poor neighborhoods. This is a pattern that has repeated itself throughout the country, and it needs to stop. Transit does not need to be “sexy,” it needs to be efficient and serve those who actually need it, not those who practically need to be paid to ride.

On the other hand, I disagree with your side comment about zoning to the extent that it implies that we need more zoning to ensure mixed-use development. In practice, zoning more often tends to inhibit mixed-use development and impose suburban development schemes in urban areas. I am always citing examples where neighborhood busybodies are trying to keep businesses from moving in near residential areas due to parking issues, etc.

It’s all artificial. And Portland’s “government subsidies and manipulation of land-use controls” have been so wildly, out-of-control successful that people keep moving there… why?… wait for it… the quality of life!

After the recession hit Portland had the highest unemployment rate of any major city in the country. Oh, and its population growth has been slowing for years:

http://www.oregonlive.com/pacific-northwest-news/index.ssf/2010/11/portland_state_estimates_oregons_population_slowing_again_with_fewer_migrants_more_deaths_than_birth.html

This isn’t about Portland, really, but I don’t think Portland is good example of urban planning if you actually look at the numbers.

Oh, sorry, I forgot something:

“in many cases ‘transit-oriented development’ has been pushed artificially with government subsidies and manipulation of land-use controls (see Portland, for example)”

It’s all artificial. And Portland’s “government subsidies and manipulation of land-use controls” have been so wildly, out-of-control successful that people keep moving there… why?… wait for it… the quality of life! Wow!

Bah. It’s a brand. Plain and simple. Driven more by tourism than local use, therefore the wealthy and middle class are rarely if ever enticed. They could care less just so long as they can park their brand new Mercedes with out of state plates in an illegal driveway between the city street and the city sidewalk. Care to take a tour with me some time?

At a certain point the titty twisting of gasoline prices and insurance will tip. And people will invest in an umbrella and some comfortable shoes, a bicycle, the grand dame of regional transit – or all three. Forgive it its nostalgic attachments and respect its future. The tax dollars and jobs it will generate will span generations.

When I try to ride a streetcar in this town, I run into three problems generally:

1) There are always a lot of people on the streetcar (which is good for ridership if not my personal comfort),

2) There is generally a long wait between streetcars, and

3) The streetcars take a long time to get anywhere due to the high number of stops.

Strange, I run into the same sorts of problems when I take buses. A little better planning could go a long way to address those, increase ridership through more consistent and dependable mass transit, and provide more return on investment. I know that if I had access to more consistent, dependable and speedy mass transit, I would use my vehicle far less than I do now.

But when it comes to the capital costs of building and maintaining roads vs. streetcar lines, let us not kid ourselves – the fantasy land cost-benefit analyses come into play with roads.

Y’all may not be used to it in New Orleans, but I come from a place where no one ever saw a road project they didn’t like. In this land of massive concrete projects the pitiance of the gasoline tax doesn’t make a dent in the DOT budget – when a gasoline tax exists at all.

As far as streetcars are concerned, they will really provide the return on investment when gasoline runs up over $5 per gallon, and people are looking for alternatives.

Mass transit ridership increased 14% even in auto centric Atlanta the last time gas was over $4 a gallon. As prices continue to rise due to increased demand, you can expect more folks to ride transit, and buses to cost more. You can also expect the politicians, fearing voter backlash over high gasoline prices, to gut road and transportation budgets as they fall over themselves lowering gas taxes so they can appear to be doing something about a problem they cannot control.

We can invest now and benefit, or we can invest later when it costs far more to do so.

Cousin Pat,

We’re completely agreed that both streetcars and buses need to be better managed. I think that the situation has improved somewhat since Katrina, but it’s still not great. I might disagree on some of your criticisms, though. For example, I don’t think the problem with streetcars is the high number of stops. The number of stops is a negligible factor compared to the long wait between streetcars.

However, we mostly disagree on roads. Sure, road projects can be subject to the same cost-benefit problems as transit, but it’s not to the same degree as with rail. There are very, very few rail transit projects that could actually pass a cost-benefit analysis. I don’t think that’s the case with road projects.

And on streetcars, I have to say you’re simply wrong. The gasoline costs of buses, even when gas is expensive, are small compared to the capital costs. Moreover, you seem to forget that streetcars are powered by electricity produced from fossil fuels. The costs go up either way. The idea that rail transit is exempt from rising fuel prices is simply wrong.

The long wait between streetcars causes more people to stack up waiting for streetcars causing the streetcars to stop more often increasing the long wait between…. A better plan with fewer stops and more streetcars would address both concerns.

As far as expense is concerned, the higher the cost of gasoline is, the more the ROI and cost-benefit analysis are going to support streetcar development as a part of urban transportation. This is especially true if your plan is to increase the walkability of your urban area, transportation options of your population, and your general quality of life. Most of the power we have in this country is provided by coal and nuclear power. Buses are very cost effective right now, and should be used in any sane transportation model, but they rely directly upon gasoline. That price is only going up in a way that coal and nuclear are not.

You also need oil to make blacktop. Even the patchwork resurfacing projects New Orleans considers “road work” increase in cost as oil increases in cost.

Streetcars were the primary urban transportation model back when the internal combustion engine was too expensive, and I suspect it will make a return in importance once the ICE again becomes too expensive, or at least reaches a level where a critical mass of the population no longer chooses to drive personal vehicles to work out of economic concerns.

Owen your pompous ego is showing itself again. New Orleans is by far not the only city rebuilding a streetcar infrastructure. Atlanta is going to build out a download line to help Ga State students and residents in the area of downtown. Dallas has a line that has been well received. They are cheaper to build than heavy rail and they do encourage development along urban corridors.

Stick to the law and stay out of urban planning. You don’t have a clue

Nicole,

I never said that New Orleans was the only city building rail infrastructure. In fact, I acknowledged that other cities were building modern light rail that is even more cost-ineffective versus buses than streetcars. In both Dallas and Atlanta — the examples you cite — light rail has been a failure, a financial drain on transit agencies that continue to hemorrhage riders versus other transportation modes.

What I find “pompous” is the refusal to look beyond a rail fetish to look at the actual nuts and bolts of how people are transported.

Owen, did you get a chance to browse the articles I linked about mass transit in Atlanta? Because light rail hasn’t been a failure in Atlanta, road building has been a failure in the Atlanta. Traffic and dependence on roads are literally strangling that city’s economy, and the real estate collapse (based on the suburban and exurban model of cheap gas and more roads) destroyed Georgia’s banking and construction economy.

Georgia was going to have to borrow $3 billion, on top of their already heady roads budget, to maintain their current roads infrastructure. This takes another budgetary hit whenever they suspend the gasoline tax.

But when gasoline goes up over $4 a gallon, mass transit ridership increases 14% despite the fact that few commuters in metro Atlanta have access to buses or rail. If they had made any sort of investment to connect the commuter rails to Gwinnett county, you could probably add another 10% on top of that.

i use the streetcar all the time. if they actually build this new route it will save me a lot of walking from Canal St. to the Marigny. i can’t take the bus because they stop running after 11 pm or so. it maybe more cost effective to run a bus line or two 24 hours a day…but unless they do that the streetcar is my only option…

Jason,

it maybe more cost effective to run a bus line or two 24 hours a day…but unless they do that the streetcar is my only option…

THIS! This is what I’m getting at. For the cost of installing and maintaining a streetcar line with spotty service, the city could probably fund a 24-hour bus with short wait times. Buses are simply cheaper. There might be other reasons why we would install streetcars instead — aesthetics, tourism (which affects farebox recovery), traffic (if streetcars can be installed in a neutral ground) — but if you just want to get people around cheaply, buses will almost always win. My main point is that we need to keep this fact in mind.

My issue is this: I will wait for a streetcar for a ride downtown and will sometimes end up waiting longer than it would take me to just walk.

Simple solution: develop a smartphone app that works in conjunction with GPS transmitters which would be installed on buses and streetcars. All you would have to do is look at a map on your phone and it would tell you where the next streetcar is bus is on a specific route, and the rider could time accordingly.

If they were able to do it for Mardi Gras parades this past year, then why can’t we have the same technology implemented on public transit systems?