Kristine Froeba, Uptown Messenger

Author Macon Fry in front of his batture home.

Macon Fry sat on his deck on a spring afternoon, above the swirling waters of the Mississippi River. Fry is weathered, composed and about to share an amusing find stumbled upon while researching his book — but he’s interrupted by a goat.

Actually, two. Both goats have the run of the front porch and plank bridge that leads from the levee, over the water, to his front door. The goats begged for a snack, which Fry attended to. Then we went back to talking about the batture, where he’s lived since 1986.

“I was spellbound the first time I met someone who actually lived here, on the river,” recounted an incredulous Fry. “And you know, most people in the city don’t even know the word ‘batture.’ They certainly never looked at the river as a place to live.”

Fry is the author of the book “They Called Us River Rats: The Last Batture Settlement of New Orleans,” a meticulously researched history of what can only be called a lost civilization.

Chapters in the book include Faulkneresque titles like, “The Other Side of the Other Side of the Tracks” and “Becoming a River Rat” and “Broken Levees, Big Shots, and Bird Men.”

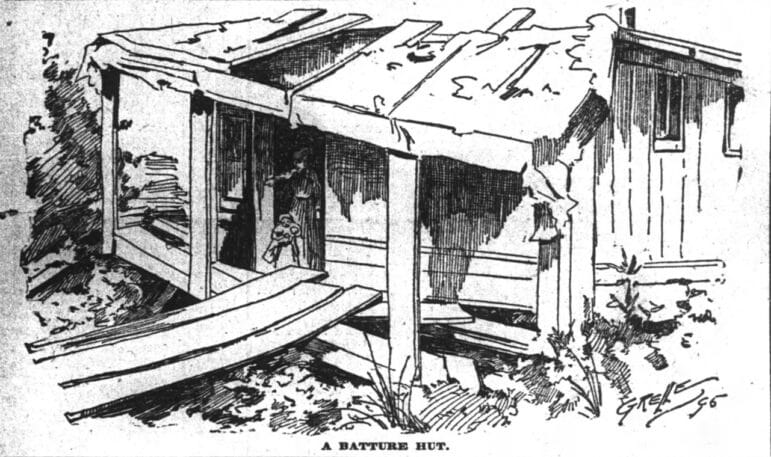

The first mention Fry found of people living on the river was in the 1891 New Orleans DailyPicayune, he said. The story is about a “queer little city built on the batture.”

The story is colorful, riveting and very long, describing six miles of houses and commerce that once flourished on the riverfront and clearly piqued the newspaper’s editors. “Everyone has heard of the slums of New Orleans … but who has ever heard of the Riverside Dwellers,” it reads, “… a unique class amongst the large horde of poor and destitute denizens of the Crescent City.”

I think it amuses Fry that he lives amongst the remnants of a modern horde of riverside dwellers.

Out of the hundreds of houses that once perched precariously on river silt, only a few remain. Centuries of storms, currents and dirty politics took their toll on the communities.

The tiny hamlet of houses is just over the levee, near the parish line, on an eastside stretch of the river known as Southport. It’s where Fry rebuilt his batture house after his original shanty fell in the river during a construction mishap.

“I moved to New Orleans in 1981,” Fry said. “Like most people, for the food and the music, street culture and friendly people, but also to get out of the rat race. Like they used to say: If you can’t make it in New Orleans, you can’t make it anywhere.”

Illustration from “Shantytown by the Riverside,” The New Orleans Daily Picayune, Aug. 4, 1895

A lost world outside the levee

The batture is that sandy stretch of land on the side of the levee most New Orleanians don’t see, the river side. Sadly, editorials like the ones mentioned above laid the framework that would lead to the eventual demise of the batture settlements.

However, 150 years ago, the area held a thriving community, a village of sorts, Fry said. A man could jump a steamboat or a barge, work a full day, come home, and never see the other side of the levee before he laid his head to rest.

Families could raise food and fowl, shop and cook without ever once leaving the maze of interconnected elevated wooden walkways and docks that hovered over the river.

Even until the 1970s, large populations continued to exist and thrive on the batture.

Why the batture?

Fry said the spark to write his book began after he stumbled upon a sign urging neighbors to bring rakes to clean and beautify an Uptown dog park on the levee. He joined in and was intrigued by what was produced — piles of cookware, antique tonic bottles and enameled pots, the archeological remains of a lost New Orleans. He wanted to know who used these implements, who cooked the gumbo in the pots.

“That was one of the many layers that really inspired me to start looking for the story,” Fry said. “The batture was one of the few places here, where there was still some archeological remnants left.”

The idea really began to take off after the author assisted with hurricane debris cleanup in Little Woods off Hayne Boulevard in the 1990s. He remembers sitting on Lake Pontchartrain’s shoreline, looking at the bare pilings that once supported dozens of houses and trying to imagine the now destroyed neighborhood.

‘River Rats’: Chronicle of a community’s demise

“The great teardown of 1954″ is laid out, when 62 families — hundreds of people — were evicted en masse from a stretch of river between Burdette Street and Jefferson Parish.

Fry also describes the demise of the last remaining batture settlement behind Audubon Park. It consisted of a large and close-knit society of Black families who worked on the river and whose community was bulldozed from civic memory after a flood in 1973. A victim of fate, commerce and, some might say, gentrification.

The book also delves into the modern challenges of those who continue to live on the river. Lawsuits, attempted land-grabs, loose barges and floods are only some of the issues faced.

All of this and more is chronicled and examined in the book, that and the personal journey of the author and his fight to remain on the river, bothersome goats and all.

Technically, it’s not located Uptown. It’s in Old Jefferson. It’s on the other side of the Parish line. JH