Courtesy of the National World War II Museum

Lawrence Brooks celebrates his 112th birthday on Sept. 12 with friends and his daughter Vanessa, left.

Central City resident Lawrence Brooks, the nation’s oldest living World War II veteran at 112, is back at his home after a recent stay at the Veterans Affairs Medical Center and a few nights in the intensive care unit.

When his daughter and caregiver, Vanessa Brooks, was notified of his impending release last Thursday (Nov. 4), she was asked whether she planned to ride home with him in the ambulance. She shook her head and laughed.

“He’ll have six people with him,” she said. “Local EMS team members argue to ride in the ambulance with him. There’s no room left for me.”

Such is Brooks’ popularity in New Orleans. Before the Atlanta game on Sunday, the Saints sent Brooks VIP tickets to a suite in the Superdome, but he was too worn out from his recent hospital stay. He watched the game from home wrapped in his favorite black-and-gold Saints throw.

Kristine Froeba, Uptown Messenger

Lawrence Brooks, 112, holds his 91st Engineer Battalion pin at home in Central City on Sunday (Nov. 7).

While he was in the hospital, Vanessa Brooks shared that what her father wanted most was an Army uniform to replace the one he’d lost in the floodwaters after Hurricane Katrina. This reporter saw that a local family donated one.

His new khakis — a reproduction of the uniform he wore while serving in World War II — were presented to him in the ICU and proved a hit. He hopes to be wearing them today (Nov. 11) for Veterans Day, perhaps on his front porch. But, unfortunately, his health isn’t what it was, so that may or may not happen.

He smiled holding the components of a uniform he wore a lifetime ago. He especially enjoyed turning his garrison cap over and over in his hands. “This is the uniform I wore in Australia,” said Brooks, placing the cap on his head.

His uniform’s ribbons and decorations were also lost in the 2005 floodwaters. His replacement insignia badge is from his old unit, the 91st Engineer Battalion, a predominantly African-American unit that served in Australia, Papua New Guinea and the Philippines. Brooks proudly relays his unit’s motto: “Acts, Not Words.”

On a call to the 91st Battalion’s headquarters in Fort Hood, Texas, a mention of Brooks’ name was met with instant recognition. When apprised of the lost decorations, the brigade’s public affairs officer immediately began a personal search to replace Brooks’ campaign ribbons. A challenge coin and a special letter of appreciation signed by the command were mailed post-haste to Brooks’ home on Saturday (Nov. 6).

Boxes of donated medical supplies, a new walker and a host of other items for Brooks are stacked up in the living room of his daughter’s Central City shotgun. They are gifts he received for his 112th birthday in September, celebrated with a party thrown by the National World War II Museum.

In addition, he is currently the beneficiary of a GoFundMe campaign to cover medical expenses and his care, so that he can remain at home with his daughter.

Brooks prefers to be cared for by family, Vanessa Brooks specifically. She said he eats better if she’s around and frets when she is gone. It’s a tough balancing act for her, but her father comes first.

The son of Louisiana farmers and one of 15 children, Brooks was born in 1909 just north of Baton Rouge in Norwood. He was raised in Mississippi outside of a small sawmill town, where his family moved to farm and work during the Depression.

By the time he was first drafted in 1940, he was living on Magnolia Street in Central City with his Aunt Lizzie and working at a service station.

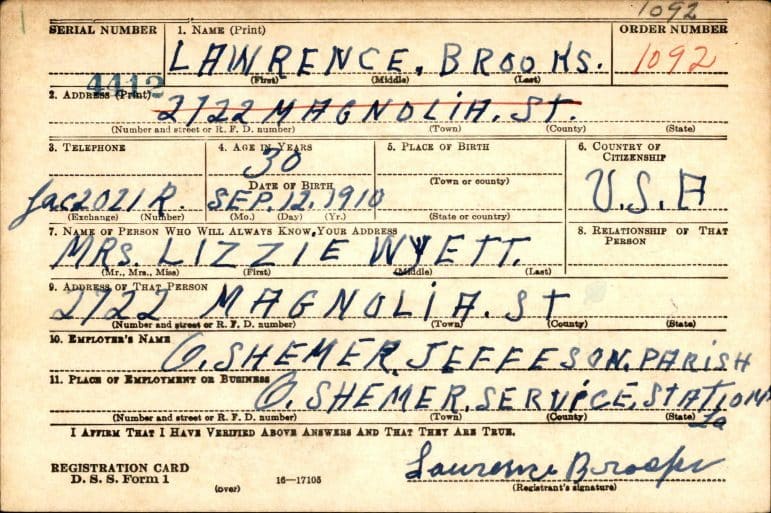

via ancestry.com

Lawrence Brooks’ original draft card from 1940. His birth year was mistakenly calculated as 1910.

When the now supercentenarian reported for duty, he served in both Louisiana and Texas. In 1941 he trained in the famed Louisiana Maneuvers — a response to Germany’s invasion of Europe. At the time, an unheard-of 400,000 soldiers converged for military exercises near Fort Polk and Shreveport.

Brooks completed his year of service and was back at work in New Orleans by November 1941. A few weeks later, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor. “There was no question,” said Brooks in one of his many oral history interviews. “They just came right back and got me again.”

He was sent to Camp Shelby in Hattiesburg, Mississippi, where he was assigned to the 91st Engineer Battalion. The unit comprised more than a thousand African-American soldiers and just over two dozen White officers. After an overland journey and inoculations in Fort Indiantown Gap, Pennsylvania, Brooks said, he found himself sailing out of New York Harbor aboard the Queen Mary.

U.S. Navy photo via Wikimedia

The Queen Mary, photographed in 1945, was placed into service carrying troops during World War II.

At the time, the former ocean liner had been converted to a troop carrier ferrying U.S. service members overseas. Some records dispute the name of the vessel Brooks shipped out on, but Brooks is adamant that he sailed on the Queen Mary and had an inside berth. He also has vivid memories of crossing through the Panama Canal. After a stop in Brisbane, his final destination was Australia.

Brook’s unit arrived in Townsville, Australia, in April, only a month before a historic racial insurrection occurred in the small Queensland military outpost. The soldiers in the 96th Engineer Battalion, another predominantly Black unit, angered by their ill treatment, rose against their White officers. Historians say the battle between Black and White troops lasted for over eight hours and that more than 600 men could have been involved. The riot, known as the Townsville Mutiny, occurred in a rural area about an hour away from Brooks’ battalion — both units were camped in outlying regions building airfields for the war effort.

The U.S. and Australian war offices censored the story, and it was lost to history for over 70 years, until Townsville historian Ray Holyoak uncovered the insurrection in 2012. When asked, Brooks said he remembers restrictions were imposed on his battalion following “something that happened over there,” pointing over his shoulder. However, he said, he doesn’t remember what occurred.

Kristine Froeba

Lawrence Brooks wears his new Army uniform in the VA hospital on Oct. 30.

When discussing the war, he prefers to reminisce about the good times, mostly about the Australian people he encountered. “Oh, they were really nice,” Brooks said. “I really liked them a lot, very friendly people.”

With incredulity in his voice, the native of the Jim Crow South related there was no racial segregation in Australia. He frequented restaurants, bars and hotels without restriction. “That’s what I didn’t understand,” Brooks said. “The Australians treated us like our own people treated us.”

He was delighted to talk about a particular Australian woman and her family in Townsville. He spent his time off at her family’s house and was a fixture at their hotel’s restaurant in town. “I had a lady friend there,” Brooks said. “Oh, I used to go to her father’s place and help deliver the liquor to their bar at the hotel.”

Brooks didn’t see combat. Instead, he said, he was a driver, valet and cook for three officers: two lieutenants and a captain. Because of his position, he was one of few members of his unit allowed the freedom to explore while his officers worked at the various military war offices and visited the Officer’s Club, all located in Townsville.

“They were good to me; I liked them,” he said. “They were nice and let me do what I wanted. I got to go places and drive them into town.”

Brooks likes to relay a favorite war anecdote while island hopping the Australian Territories in a C-47 . He said they lost an engine and began flying low over the water. The navigator walked back into the airplane and began dumping barbed wire cargo to lighten the load. Brooks said that he got up and headed to the cockpit before being stopped. He laughed when he retold the response he gave his sergeant.

“My sergeant wanted to know where I was going,” said Brooks, rumbling with laughter. “I said, ‘The only two parachutes on this plane are up there. If they jump out, I’m grabbing onto one of them.'”

Most of his anecdotes are filled with laugher. One gets the impression there is much to tell, but Brooks focuses on the positive. “We built bridges, roads, and airstrips,” he said in a previous interview. “That was our job.”

Brooks’ unit built numerous frame buildings, Quonset huts, roads, hospitals, housing, shops and recreation centers across Queensland and the outlying Australian Territories. He tells of working on Horn Island, Papua New Guinea and the Philippines. He remembers digging and diving into foxholes on numerous occasions when the Japanese strafed his unit.

“Out on Horn Island, the Japanese used to come at night,” Brooks said. “We would row out to Thursday Island and hide.” He explained that the Japanese had a cemetery on Thursday Island and wouldn’t bomb it out of respect, so the Americans would sneak over at dusk to hide until the attacks were over. He laughed when he said they watched the Zero fighter planes overhead.

Pfc. Lawrence Brooks during World War II

Brooks left service in 1945 as a private first class. In his only military portrait, he is wearing a variation of the wool “Ike” jacket. It’s all that remains from his time in the war. However, his rank appears to be higher, perhaps a sergeant.

When asked about the stripes in his portrait, Pfc. Brooks once again broke into laughter. It seems he didn’t gain or lose stripes overseas. He cackled as he said it’s not his jacket in the photo. One night, in a wartime caper, his officers decided to sneak him into the Officer’s Club for a big party and gave him the jacket and cap as a disguise. That’s his story, and he’s sticking to it.

God bless you sir, and thank you for you service, it was an honor to read your story, hope you celebrate many more year!!

What a blessing wishing him a speedy recovery