jewel bush

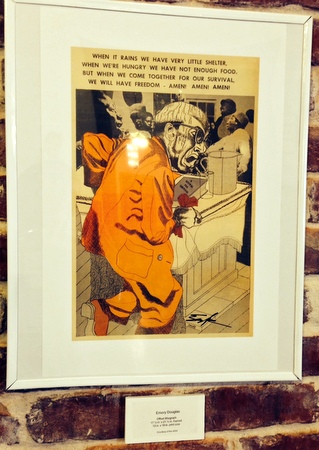

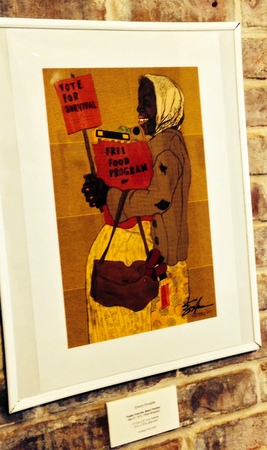

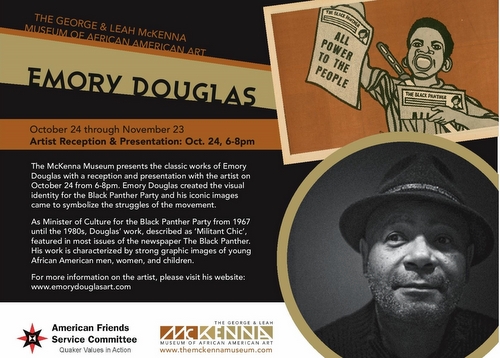

Graphic artist legend Emory Douglas — whose work is on display now at the McKenna Museum in New Orleans — is responsible for crafting the Black Panther Party’s iconic visual identity, capturing the era’s intensity through fiery artwork that rose above the rhetoric and subterfuge of the day to reach an embattled community in ways words were unable to articulate.

Douglas served as the Minister of Culture for the organization from 1967-1980. Under his art direction and production, The Black Panther, the party’s official newspaper, reached a peak circulation of more than 130,000 a week in 1970.

His job was no easy one. He was tasked with communicating complicated political messages to a community with high illiteracy rates, a largely nonreading demographic. His work needed to pack a punch, land a visual knockout, while informing and educating above all.

And Douglas delivered.

“It was something I looked forward to,” said Vera Williams, owner of the city’s only black-owned bookstore, Community Book Center, who in the fifth grade would take the one-way, hour-long bus ride from her home in the Lower Ninth Ward to Canal Street just to purchase The Black Panther every week. “If Hurricane Katrina wouldn’t have hit, I would still have all of my Black Panther newspapers from over all those years at my parent’s house.”

In his newspaper designs, posters, and leaflets, complex meanings can be extracted at a glance from Douglas’ portrayal of life in 1960-70s Oakland — and beyond — where racism, police brutality, inhumane housing conditions, poverty and pain were everyday realities. He created strong graphic images, revolutionary art, that spoke to the party’s anti-Vietnam War beliefs, its platform of self-determination for indigenous peoples all over the globe, its campaign against government corruption and its creation of social-aid programs such as free breakfast for children.

The masses — young black men, women, children and even the elderly — saw themselves in Douglas’ work through spirited portrayals of their humanity and dignity amidst their profound, bellyaching struggles. In a poster from the June 6, 1973 issue of The Black Panther, a woman donning a sizable Afro holds a youngster on her lap. Together, they flip through a periodical with the message, “Fight sickle cell anemia,” emblazoned on the cover. In the collage, “We Shall Survive. Without a Doubt,” from the August 21, 1971, newspaper, education is the message. The smiling face of a young boy wearing glasses is center stage. Scenes of children in school settings radiate through the lenses of the specs. Two other small kids share the artistic space. One gives a fist pump. The design is a nod to the Panther-run Oakland Community School, which served 200 students and had a waiting list of 1,000.

(photo by jewel bush)

Douglas, a grassroots artist who received some formal training at the City College of San Francisco, didn’t enter the community through a distant, voyeuristic vantage point, offering up condescending or patronizing depictions of the people and the crushing social injustices they faced. His work is compassionate and empowering. Douglas captures a sense of pride under even the most oppressive of circumstances portraying destitution so visceral it stings your soul.

“You have to learn to undress the issues before you can feel it in your artwork. You have to have a knowledge of what you are talking about and be able to defend it,” Douglas said in an interview at the opening last week for his showing at the George & Leah McKenna Museum of African American Art.

Douglas was rooted in the Black Arts Movement working with Amiri Baraka, then LeRoi Jones, before taking up the Panther pillar. He documented the spirit of resistance in this downright ugly chapter of American history that is often storied and revisionist in its retelling. His body of work, ranging in 200-300 images, creates this visual record.

Through inexpensive printing techniques such as mimeographs, photostats, prefabricated presstypes and screentones, along with offset printing and even ink and marker drawings, Douglas ran a fast-paced newspaper operation during a dangerous period where raids and police shootouts were the norm. Many of Douglas’ comrades didn’t survive the movement. His Black Panther activities, being the man responsible for official Panther media, made him a high-level law enforcement target and earned him spots on numerous FBI lists.

At 70, now retired from the newspaper printing business, Douglas moves with a mien of forever cool. He travels the world with his MacBook Air in tow, accepting invitations to discuss and show his illustrations, instrumental in shaping the people’s political identity while nurturing their notions of liberation. His visual commentary continues to move and inspire as a younger generation of cultural workers embrace his grassroots motifs and intrepid style. His sway can be seen in the work of Bay Area activist artists like Favianna Rodriguez and that of New Orleans activist artist, Brandan “BMike” Odums.

“I noticed all over my house that I have about six different printouts of Emory Douglas’ work on my walls. Some are from a Tupac book I got in college,” Odums said. “When I went to art school, I studied Van Gogh and Picasso but seeing Emory Douglas’ art … it was speaking my language. His art was something that made sense to me.”

(photo by jewel bush)

Many members of Odums’ generation find Tupac Shakur as a Black Panther point of reference. Whether it’s presenting at a design conference in Argentina or on tour in New Zealand or among the Zapatistas in Mexico or doing an installation at the elusive, guerilla artist Banksy’s London gallery, Douglas is sure to encounter the same question from younger fans without fail: “Did you know Tupac?”

Always a mentor to those walking the path his fearlessness and creativity helped pave, Douglas tells them, “Stay focused. It’s an ongoing process, and don’t fear critique.”

Douglas still enjoys an active career as an independent graphic artist. He explores themes like drone warfare, the prison industrial complex and Guantanamo Bay in his art; but unfortunately, many of the same issues he addressed some four decades ago – police brutality, hyper incarceration of black men, food instability, lack of quality healthcare for poor people, lack of affordable housing — persist today.

“As much as things change, things stay the same,” Douglas said. “You can tweak some aspects of the artwork … add the name of another corporation, and you have the same issues decades later.”

And the answer is, yes, he did know Tupac. Tupac’s mother, Afeni Shakur, was a member of the Black Panther Party.

See “The Classic Works of Emory Douglas” at the George & Leah McKenna Museum of African American Art, located at 2003 Carondelet St., 70130, through November 23.

jewel bush, a New Orleans native, is a writer whose work has appeared in The (Houma) Courier, The Washington Post, The Times-Picayune, New Orleans Homes & Lifestyles Magazine, and El Tiempo, a bilingual Spanish newspaper. In 2010, she founded MelaNated Writers Collective, a multi-genre group for writers of color in New Orleans dedicated to cultivating the literary, artistic and professional growth of emerging writers. Her three favorite books are Their Eyes Were Watching God, The Catcher in the Rye, and Are You There God? It’s Me, Margaret.

The black panthers make the KKK look like boy scouts.

They are the single most racially divisive group of black men and women in the Country.

Its no surprise they are tightly aligned with the Nation of islam.