The 400th anniversary of Africans being brought to America as slaves was on my mind last Sunday when I read the obituary of the late Yorke Nicholson Corbin, a former reporter and member of the family who owned the Times-Picayune and its predecessors for almost 100 years.

His father, Carl, was editor of the New Orleans States and editorial editor of the New Orleans States-Item. His mother, Eleanor, was a former amusements editor and columnist. His grandfather Yorke P. Nicholson was a vice president of the Times-Picayune Publishing Co. His great-grandmother Eliza Jane Poitevant Nicholson, a poet who wrote under the name “Pearl Rivers,” was the first female publisher of a major American newspaper. Although not actively engaged in slavery, like many New Orleanians whose family roots stretch back to the antebellum era, Corbin and The Times-Picayune have an indirect connection to the buying and selling of humans.

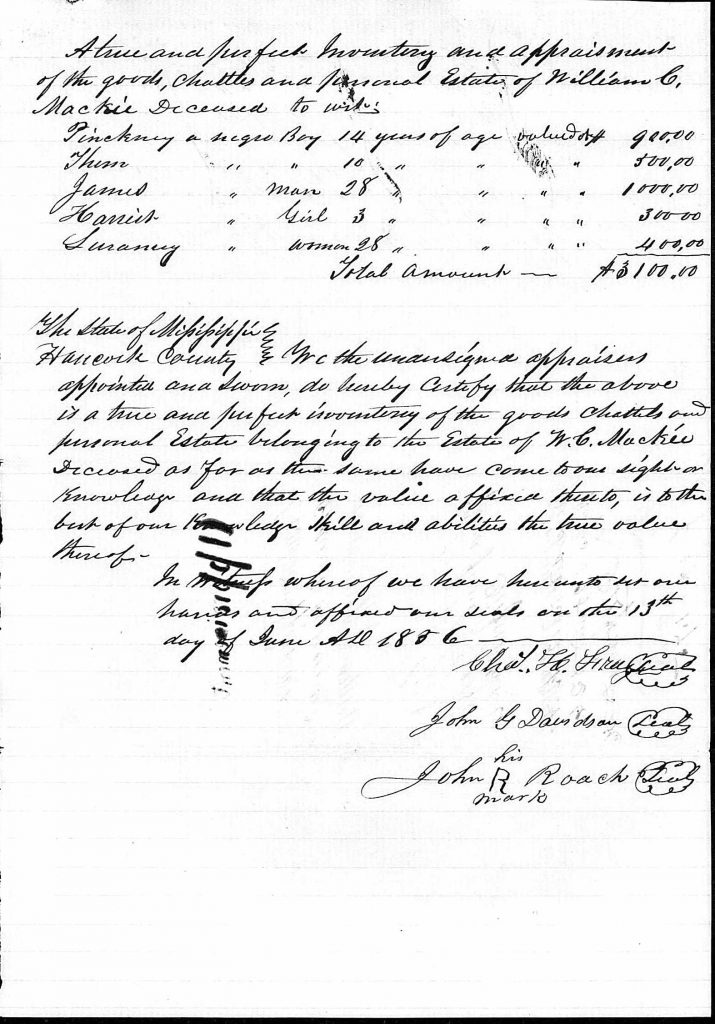

Mississippi businessman William C. Mackie’s slave inventory. Click image to enlarge. (Hancock County, Mississippi, probate records)

While many readers are probably familiar with Eliza Nicholson and the role she played in American history, they are less familiar with her father — William J. Poitevent — an 1850s lawyer in Hancock Country, Mississippi. When white Mississippi businessman William C. Mackie died in June, 1856, Poitevent oversaw the auction of Mackie’s five slaves to a Hancock County physician Thomas Charles Leonard Sr.

Among the family members sold were an adult female, Lurany Mackie, who fetched $400 and her 3-year-old daughter Harriet, who brought $300. Harriet had a bi-racial daughter who met and married a man of French descent in Bay St. Louis, subsequently moved to New Orleans and became the matriarch of one of our city’s most important political families.

If the descendants were to meet at a New Orleans cocktail party, should Eliza’s great-grandchildren apologize to Harriet’s great-grandchildren?

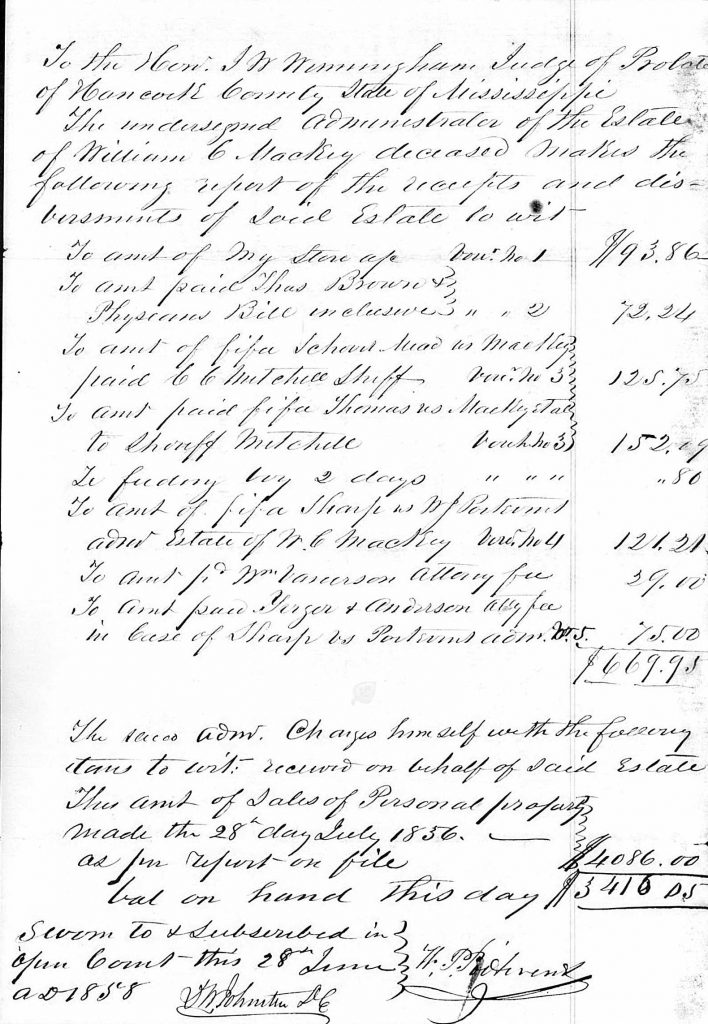

William Poitivent is made administrator of Mackie’s estate. Click image to enlarge. (Hancock County, Mississippi, probate records)

Eliza Nicholson was able to pursue her passion as a poet because her father provided a comfortable life due in some part to his role in successions at a time when slaves were considered property. Poitevent may have even owned slaves.

Harriet and her children did not benefit from any luxuries. Undoubtedly, Harriet was elated when her daughter found a good husband capable of providing a financially secure future for their growing family. When Harriet’s daughter first arrived in New Orleans, she listed her ethnicity as white of Hispanic descent. In later census records, she and her children were listed as white.

Slavery did not begin with those 20 Africans brought to Jamestown, Virginia, in 1619 by Dutch traders who had seized a Portuguese ship. Since the ancient civilizations of Greece, Rome and Egypt, winners on the battlefield frequently forced losers into slavery or the gladiator arena. Several early Catholic popes were slave owners. Frequent raiding expeditions by West Africans netted tribesmen from other Central and West African nations who were quickly sold to Arab and West European slave traders.

Poitivent oversees the sale of the McKay estate. Click image to enlarge. (Hancock County, Mississippi, probate records)

Slavery in America was different than ancient slavery. Never in the history of the world were a group of people kept for generations for the sole purpose of economic gain. Much of the wealth of Deep South cities like New Orleans was accumulated on the backs of slaves and perpetuated by systems that passed those riches down to slave owners’ children and grandchildren.

New Orleans free-people-of-color, as well as Creoles, often owned slaves. Proponents of reparations believe that this accumulated wealth must be redistributed to the descendants of enslaved Africans either through cash awards or other incentives. “We must create a pathway for justice,” said one civil rights leader. Opponents argue that descendants live a better life in America than in their ancestral homes.

If the concept of 40 acres and a mule had applied to descendants of enslaved Africans after the Civil War, those families could have used their skills to build generational wealth. Instead, America’s ghettos are still filled with families who could never catch up.

Polls continue to show that the majority of Americans are not convinced that repayment for historical injustices is necessary. In an April 2016 Fox News poll, 60 percent of Americans opposed paying cash to black Americans who could prove they descended from slaves, while 32 percent supported it. A Rasmussen poll taken the same month indicates that only 21 percent of likely voters thought public funds should be used to pay descendants.

The answers become more complex when respondents are segmented. Voters under the age of 45 are more favorable toward payments, according to a Data For Progress poll. As reflected in a 2016 Point-Taken Marist poll, six out of 10 black Americans support reparations. Among Democratic primary voters, 54 percent said they are likely to support a presidential candidate who backs reparations. While President Trump clearly opposes the concept, Corey Booker, Bernie Sanders, Kamala Harris, Beto O’Rourke and Tulsi Gabbard are voicing some level of support. Elizabeth Warren has suggested that Native Americans must be included in the discussion.

According to the New York Times, American citizens previously received compensation for historical injustices including Japanese-Americans who were interned during World War II; survivors of police abuses in Chicago; victims of sterilizations in North Carolina; and black residents of a Florida town that was burned down by a murderous white mob. Members of federally recognized Native Americans tribes received $1.3 billion but were not pleased that the U.S. government retained oversight of the funds. In 1971 Alaska’s Indians, Eskimos and Aleuts received $962 million for some 44 million acres in return for relinquishing aboriginal claims to the rest of the state.

Reparations are “a challenging issue” said House Speaker Nancy Pelosi recently. Yet, it is the responsibility of the federal government to eventually resolve the debate. Even after the 2020 presidential and congressional elections, Democrats and Republicans will continue to view the issue through different lenses. While formal apologies by state and local governments could increase, compensation of any kind is not on the horizon. In the meantime, many descendants of those who profited from the slave trade enjoy a higher standard of living than descendants of those enslaved. Is that what some people consider the “American Way”?

Danae Columbus, opinion columnist

Danae Columbus, who has had a 30-year career in politics and public relations, offers her opinions on Thursdays. Her career includes stints at City Hall, the Dock Board and the Orleans Parish School Board and former clients such as District Attorney Leon Cannizzaro, City Councilman Jared Brossett, City Councilwoman-at-large Helena Moreno, Foster Campbell, former Lt. Gov. Jay Dardenne, former Sheriff Charles Foti and former City Councilwomen Stacy Head and Cynthia Hedge-Morrell.