(via conservativesconcerned.org)

While abolition of the death penalty has long been considered a liberal policy goal, a new group of conservatives activists say it fundamentally conflicts with their view of a limited government, and they are now organizing an effort to end its practice in Louisiana.

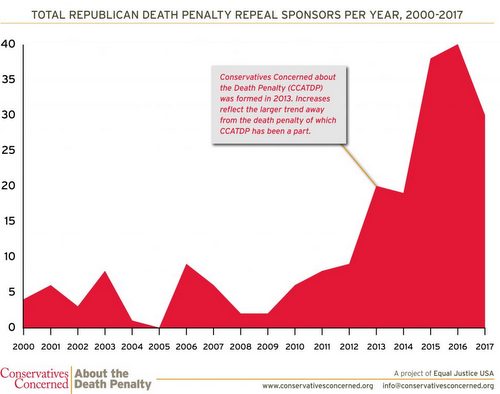

In 2013, the number of Republican lawmakers proposing legislation to end the death penalty in their states more than doubled from single digits to 20, and doubled again in in 2016 to 40, according to a group called Conservatives Concerned About the Death Penalty, which sponsored a forum on the issue Thursday evening at Tulane University. Likewise, nearly a third of the co-sponsors of bills abolishing the death penalty were Republicans in 2016 and 2017, up from nearly zero a decade ago, the group’s research shows.

Louisiana is among those states, with legislation to eliminate the death penalty in 2017 sponsored by Republican state Sen. Dan Claitor of Baton Rouge, whose conserative bona fides include honors from the Louisiana Family Forum. Claitor’s stated views that the death penalty is expensive and ineffective fall right in line with the thinking being adopted by many other conservaties, said Hannah Cox, a national organizer for Conservatives Against the Death Penalty.

Cox was still strongly in support of the death penalty when she first began working in conservative politics, she told the crowd at the Tulane panel. But when asked to research a bill regarding the death penalty for the mentally ill, she began to examine the policy’s effects for the first time, and became convinced that it contradicted her conservative principles.

“People who have never been to prison think that life is the most valuable thing they have, but it’s actually freedom,” Cox said, noting that many death-row inmates give up on the appeals process and submit to execution as a way of ending their incarceration. “When you lose your freedom, you realize that.”

Michael Cahoon, a local organizer for the progressive Promise for Justice Initiative, said he was asked to join the penalty to provide the “liberal” perspective on the issue. But raised as a Catholic opposed to it for religious reasons, Cahoon said he feels the issue fits clearly as a conservative one.

“I actually think the conservative case against the death penalty is much more direct — a limit on government power,” Cahoon said.

Cox and Cahoon laid out a number of objections to the death penalty:

- It has great potential for error, possibly resulting in the government putting an innocent person to death. Nearly 1 in 10 people sentenced to death have subsequently been exonerated since the penalty was reinstated in the 1970s, Cox said.

- It is too expensive, with millions spent by each death-penalty state on their cases every year that could be redirected into law-enforcement. Many critics of the justice system focus on the lengthy appeals process in death-penalty cases, which can drag on for decades. A study in North Carolina, however, showed that the 70 percent of the cost was incurred during the initial trial and sentencing phase, because the state must pay for so much more forensic testing and specialized experts to even seek the conviction.

- It is not a deterrent. States with the death penalty regularly see higher rates of violent crime than those without it. Meanwhile, most law-enforcement experts agree that the best deterrent to crime is the perceived likelihood of arrest — thoughts of eventual sentences are far more abstract and unlikely to play a role in a heated moment.

- It is applied seemingly at random. Many people say they support it only for the “worst of the worst,” but it is much more commonly applied to routine crimes. Many serial killers plead to life in prison, and the death-penalty was not even sought for 9/11 co-conspirator Zacarias Moussaoui, for example.

- It is racially biased — usually around the race of the victim, even moreso than the race of the criminal. The last time a white person was put to death in Louisiana for killing a black person was in 1752, Cahoon noted — and that was a slave considered property, so the sentence was actually applied for destruction of property, not for killing a person.

That disparity, Cahoon said, shows that the implementation of the law implicitly values the lives of one racial group more than another — a direct contradiction of nearly anyone’s values imaginable. - It does harm to victims of crime. A death-penalty trial is frequently the worst thing that can happen to crime victims, Cahoon said. Every development becomes front-page news, often for two decades while the lengthy appeals run their course.

“A lot of people put the healing process on hold until the legal process is finished,” Cahoon said. “In the death penalty, that process could be 30 years. It could be never.”

The death-penalty opponents found few critics in their audience of 50, most of whom were college-aged. One man questioned whether isolating death-row inmates makes the general prison population safer, but Cahoon and Cox said that there is little evidence that the murders placed on death row are more dangerous than those who plead to life, and that better measures can be used to ensure safety in prisons anyway.

While some opponents of the death penalty envision a sweeping federal decision to repeal it, Cox said that Conservatives Concerned About the Death Penalty has decided that a state-by-state approach is more effective. For one thing, a single federal decision abolishing it could be overturned by a subsequent federal decision, essentially reinstating it yet again. State-level actions, by contrast, would have to be overturned individually.

The effort is also playing out in state legislatures — and must do so in Louisiana, Cahoon said, where the state Constitution does not lend itself to challenging the death penalty through a court decision. Claitor has already begun building allies for his work in Baton Rouge, however. His 2017 bill passed a Republican-majority committee, and both state Sen. J.P. Morrell and state Rep. Terry Landry (two Democrats) have introduced similar bills — and activists predict the Catholic Church, opposed to the death penalty for decades, can be a particularly influential ally in the state.

“It’s not partisan, or bipartisan, even. It’s nonpartisan,” Cahoon said. “Especially in Louisiana, you have nonpartisan reasons that really bring people together.”

In order to support those efforts, Conservatives Concerned Against the Death Penalty is forming a chapter specifically for Louisiana, Cox said. They hope to have the structure in place by the end of the year, so they can begin work during next year’s legislative session.