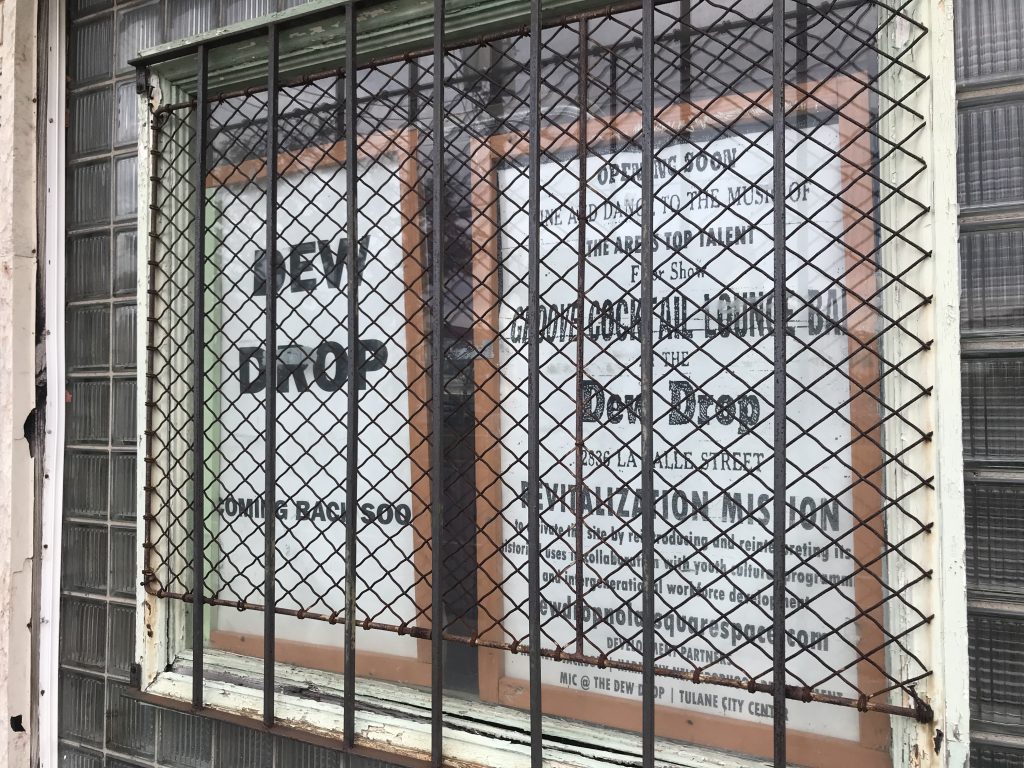

The Dew Drop Inn at 2836 LaSalle St. in Central City remains vacant, as it has since 2005. A developer with a sale pending on the property hopes to revitalize the space, bringing it back to life with 15 hotel rooms, a music venue and a museum. (Nicholas Reimann, Uptown Messenger)

By Nicholas Reimann

“Oh baby, Dew Drop Inn. I’ll meet you at the Dew Drop Inn.”

Those are words you might soon hear outside of just the 1970 Little Richard song “Dew Drop Inn,” as a developer takes the first steps in an ambitious project to restore the historic hotel and music hall on LaSalle Street in Central City — once a common stopping point for top African-American musicians performing in the Jim Crow South, including James Brown, Tina Turner and Ray Charles. The latter even lived in the hotel at one point.

The project’s developers had their first chance to show their proposal for a revived Dew Drop Inn to the public at a neighborhood participation meeting Saturday, Nov. 17, where they took input as well as outlined the plan for a completely renovated two-story space totaling around 10,000 square feet — including 15 hotel rooms, a restaurant, music venue and museum of New Orleans music.

A photo by Ralston Crawford shows the Dew Drop Inn in 1952. (Courtesy of Tulane Digital Library)

Rendering of the plans for Dew Drop Inn. (Courtesy of Concordia Architecture)

Uptown Messenger file photo

The Dew Drop Inn at 2836 LaSalle St. in Central City has been vacant since 2005. (Nicholas Reimann, Uptown Messenger)

Originally opened as an expansion of Frank Painia’s barbershop in 1939, the Dew Drop Inn building at 2836 LaSalle St. in Central City has sat vacant since the last few long-term tenants of its rooms were forced out because of Hurricane Katrina.

The famed music venue has been closed much longer. Painia, then in failing health, shut that down in 1970, among shrinking crowds after options increased for African-Americans following the end of government-enforced segregation. Painia died in 1972.

The property has remained with the family since, and efforts have been made to bring the building back to glory — notably by Painia’s grandson Kenneth Jackson — but the funding was never there.

The family ultimately decided to put it up for sale, posting a $600,000 listing in March that Melanie Painia — Frank’s granddaughter — said was better than “it falling to the ground and them demolishing it.”

That was about the same time Ryan Thomas had begun his real estate development company, Peregrine Interests. Thomas said he had been looking around at prospects for his first project, preferably developing a hotel or some sort of vacation rental.

Then he saw Dew Drop was on the market.

“The cultural history that this place holds is so significant. I mean, there’s so much that has gone on at the Dew Drop that it’s a treasure that deserves to be restored and brought to life,” Thomas said. “This place was a great fit for the things that I was looking for. It had a great, extra added bonus of all the history that goes along.”

Thomas said his company is set to close on the sale Dec. 30, but has a contract in place to begin development plans. He would not disclose the agreed-upon amount.

Thomas is working with Concordia — an architecture firm based out of Central City —on designs for the future of the Dew Drop Inn. The plans are still far from complete, Concordia architect Joel Ross said, adding that he’ll use input from the community Saturday in the project’s conditional use permit application, which he said was needed for the music venue and to add parking for the building.

The property is zoned as a historic urban neighborhood, which allows for a hotel, Ross added.

Current plans show a 6,000-square-foot first floor, where the music venue will be, along with the restaurant, green room, lobby and meeting rooms.

An addition will also be made along the back of the building — a side in much more serious disrepair than the front, Ross said — which will go around a pool area, another new feature.

All of the guest rooms will be upstairs, and will range in size and cost. The current plan calls for 15 rooms on the 4,000-square-foot floor — half of the 30 the hotel used to have — which will range in price from $80 to $150 a night, Thomas said.

Renting rooms will be the primary source of revenue, he added.

But while the rooms, restaurant and music space will seek to replicate the history of the Dew Drop Inn, Ross said it’s a proposed new feature that could most honor it — the museum.

A developer with a sale pending on the Dew Drop Inn hopes to revitalize the space, bringing it back to life with 15 hotel rooms, a music venue and a museum. (Nicholas Reimann, Uptown Messenger)

It’s a space Ross said is lacking in New Orleans, adding that he hopes that it might become the primary museum for New Orleans music, likening it to the Stax Museum of American Soul Music in Memphis or the Motown Museum in Detroit.

What exactly will go there is still being discussed, though, and it doesn’t look to be a large space — sharing room with the lobby area.

On Saturday, the public gave developers some ideas for the museum, like having artifacts from the old Dew Drop, historic Mardi Gras throws and a listening experience for stories told by those who saw the Dew Drop in its heyday.

One person who’s ready to talk of that heyday is Melanie Painia, who remembers the days when her grandfather was called “the mayor of LaSalle Street.”

Painia said she wasn’t old enough to see the live shows at the Dew Drop but remembers the celebrities who used to frequent it.

Ray Charles practiced piano at her grandmother’s house while he lived at the Dew Drop, she said, and her grandfather’s friend Adam West would often come to see shows.

It’s relationships like the one her father had with West — the first “Batman” in a feature film — and generally the Dew Drop’s friendliness to all who wanted to hear music there that got Frank Painia into trouble, though.

“My grandfather went to jail many times,” Melanie Painia said. “Whites and blacks weren’t supposed to mix at a certain time, and the police would come and raid the Dew Drop and bring all of them to jail.”

But the crowds would continue to come to see musicians who were performing on the “Chitlin Circuit” of clubs around the country that, like the Dew Drop, welcomed African-American entertainers during segregation.

Her grandfather at one point got so tired of the police raids that he filed a lawsuit against the city in 1964. That became moot, though, after the passage of the Civil Rights Act of that same year.

But he put in the effort because, above all, what Frank Painia wanted was a place for people to have a good time and for musicians to have the chance to put on a good show, his granddaughter said.

Melanie Painia said he would be proud to see his old club coming back to life, and she hopes that once the project is over, the city will look to put up a statue of Frank Painia — “the mayor of LaSalle Street.”

“I’m just so happy that someone is taking on this project, and I know my family … I know my grandfather would be happy,” Melanie Painia said.