New this month is a virtual exhibit that shows how New Orleans has benefited from Black leadership and engagement since the 19th century. Hancock Whitney and the Amistad Research Center at Tulane have partnered to present this curated collection, entitled “The Things We Do for Ourselves: African American Leadership in New Orleans.”

The exhibit uses Google Cultural Institute’s platform to create a virtual expansion of a past physical exhibition at the center. The virtual collection went live in celebration of Black History Month, though it was created as a free, permanent and accessible way to give back to the communities the organizations serve.

Christopher Harter, deputy director of the Amistad Research Center, said it is important for the local community to see how African American civic leadership helped shape New Orleans.

The purpose of this collection, he said, is “to educate the public about not only the historical materials that are housed in Amistad’s collections, but how these materials are relevant to the questions and issues that we’re facing today.”

courtesy of Amistad Research Center

Unity Industrial Life Insurance Company office. In 1906, the state of Louisiana passed a law to differentiate between benevolent societies and insurance companies. It defined insurance companies as businesses that employed agents to collect premiums and issue policy contracts. The first Black industrial insurance company in Louisiana was the Unity Industrial Life Insurance Company, founded in 1907. The photograph, by leading photographer Villard Paddio, is believed to be the office of Unity Life.

“We were looking to use history, quite frankly, to uplift,” added Tamara Wyre, referencing Carter G. Woodson’s main objectives in developing Negro History Week, which birthed Black History Month.

Wyre, the senior vice president and director of Diversity, Equity & Inclusion at Hancock Whitney, said her organization is always looking for ways to educate its workforce, more than 4,000 associates, and communities across the five states they call home.

“I just wanted to make sure that we were touching on all parts of who we are as a Black community and how we draw a historical contribution,” she said. “We wanted that to be shared, but we wanted to make sure to share it in a way that any and everyone could learn from it.”

Dillard University, also a collaborator on this project, is well represented in this exhibit, having celebrated 150 years in New Orleans as of 2019. “Dillard is firmly planted,” said Eddie Francis, director of communications and marketing at the university.

“[This partnership] creates awareness of the role that Dillard has played in providing a space for African Americans to develop into leaders,” Francis said. “This exhibit is sure to satisfy the public’s appetite to learn more about the African American experience, especially in New Orleans where African heritage is celebrated in the city’s culture.”

Displaying Black civic leadership in New Orleans

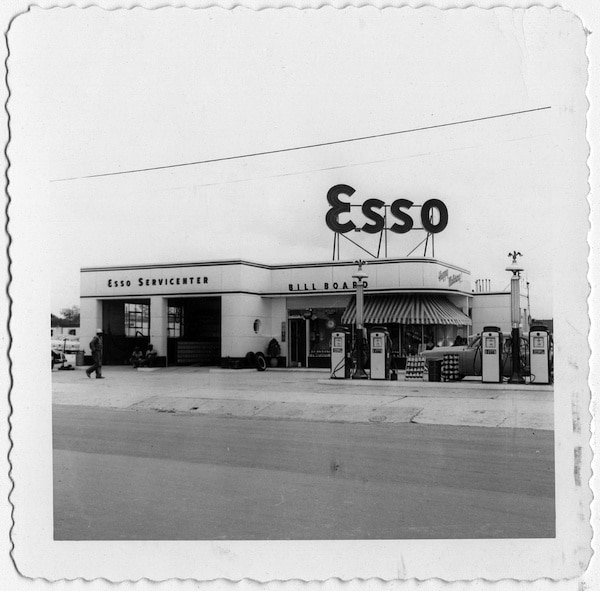

courtesy of Amistad Research Center

Marsalis’ Esso Service Station. Ellis Marsalis Sr., a prominent New Orleans businessman, began his business career in 1936 as the manager of an Esso service station, along with his business partner, William Wicker. When the station first opened, it was located at Eighth Street and Howard Avenue, but it later moved into the Uptown neighborhood.

“The Things We Do for Ourselves” uses detailed storytelling and rare images to chronicle how African-American leaders — many whose family names still ring familiar across the city and nation — championed civil rights and filled voids in countless services and resources for African-American New Orleanians.

Much of the exhibition is looking back at history, but there are aspects included that still have a presence in New Orleans communities today.

Harter explained: “We touch on the foundation of McDonogh No.35 as the first high school for African Americans in the state. We touch upon the founding of the Louisiana Weekly, which is still an important source in the community, [and] Dooky Chase, obviously an icon of New Orleans restaurant scene.”

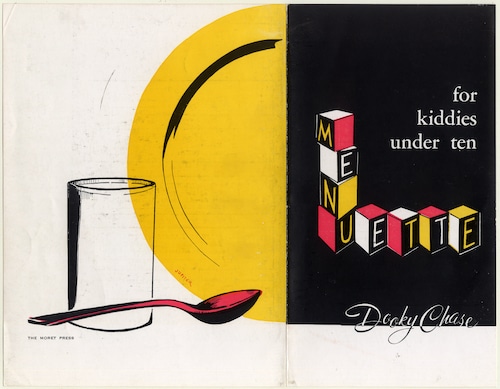

Amistad Research Center

Dooky Chase’s children’s menu. This whimsical “menuette” from the restaurant, printed by the Moret Press, testifies to the restaurant’s appeal to diners young and old.

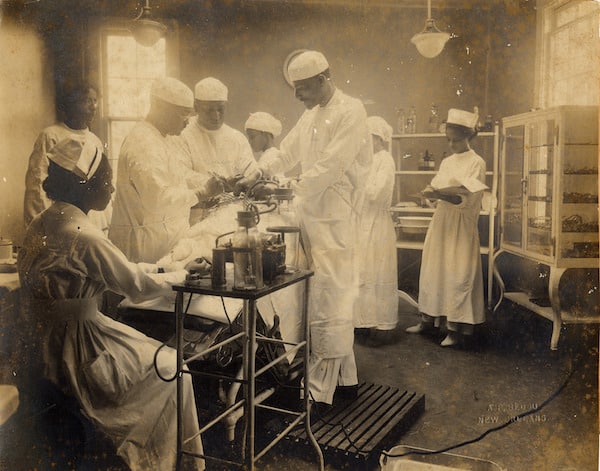

The history portrayed in this collection is timely, as many of the issues faced in the past are still around today as well. Harter uses the history of African American medical community in New Orleans as an example. He said:

“The issues that are raised in this exhibition about inequality of education in the medical field and access to medical aid… if you’re looking at what’s going on with the pandemic, these are questions that are still continuing to be raised today… So we can take a look at these documents and the materials that are in this exhibition and see, ‘how have we gotten to this point? What are some things that we can learn from the past going forward?'”

As Francis noted, “The year 2020 showed us that it’s not what the nation knows about African Americans’ contributions to leadership but what the nation doesn’t know.” He said that this exhibit offers the idea that an investment in developing African American leaders is good for all in the Greater New Orleans area, not just African Americans.

“Almost everything that the world adores about New Orleans is because people of African descent pour every drop of their souls into the city’s culture,” he said. “So, leaders throughout Greater New Orleans can leverage a vibrant higher education environment to take a kid from tap dancing in the French Quarter to becoming a future U.S. president, liberal arts scholar or corporate CEO/philanthropist.”

courtesy of Dillard University

Dillard University will host an online event that will feature narration and panel discussion with the collection’s curators.

The partner organizations will host a virtual event on Wednesday (Feb. 24). Curators from The Amistad Research Center will narrate and guide guests through the exhibit, followed by a panel discussion.

“The community will hear from African American scholars with a wealth of intellectual capital,” Francis said. Guests of all ages are encouraged to join, learn, and be inspired.

Impact

For Hancock Whitney, “The Things We Do for Ourselves” also serves as an educational experience in diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI). This work is not something that starts and stops, Wyre says; it is something you continue to evolve. The idea is to keep having those honest, respectful, courageous conversations with the intention to grow a truly thriving community.

“We want to make sure that we are pledging exceptional services to our clients and into our community,” Wyre said, ” and we believe the best way to do that is to mirror and resemble the communities where we do business, the communities we serve.”

Amistad Research Center

Sewing class at the YWCA. The papers of educator Fannie C. Williams include over 250 photographs documenting the Claiborne Avenue Branch of the YMCA in New Orleans. Williams served as an organizer, charter member and first president of the branch, which served the African American population of the city. It was located originally at 1609 N. Robertson St. prior to the construction of a new building at Cleveland and South Claiborne Avenues.

Wyre and Harter agreed that Hancock Whitney and the Amistad Research Center are looking forward to working with one another more in the future, and this exhibit is only the beginning.

“Partners such as Hancock Whitney are helping us to foster are really engaged outreach in practical ways to the community,” Harter said. “Part of our mission is not only to collect and preserve historical documents, but the key to that is providing access to these materials to researchers, to students, and to the general community.”

“The partnership really just aligned with our core values,” Wyre added. “[It] fosters an appreciation for African American contributions to the unique culture that we still love and [that] distinguishes New Orleans from all other places around the world.”

Hancock Whitney wanted to make sure to focus on inspiring and fostering Black-owned businesses, organizations, and institutions more effectively, and to aid the development of the communities they love and serve, she said.