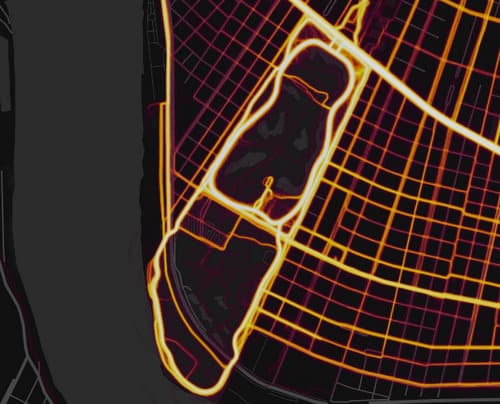

A “heatmap” created by the running app Strava shows the intensity of use by runners around Audubon Park. (via strava.com)

Representatives from groups that have fought to protect public access to open space in parks across the city united on Thursday night to call for a more unified system of governing the park system in New Orleans, saying the upcoming expiration of property taxes that support Audubon Park is the opportunity to begin such a large conversation.

The panelists — assembled by the Louisiana Landmarks Society and including representatives from Save Audubon Park, City Park for Everyone, Parks for All and others — agreed that funding for open space is difficult to come by. Further they acknowledged that the city has different groups of residents value parks for different reasons, from the opportunity to enjoy untamed nature in the wildest parts of City Park, to safe places for running and cycling on tracks, to organized sports and other activities.

The “Balkanized” system of governance of parks in New Orleans exacerbates both of those problems, however, the panelists said. With separate entities controlling Audubon Park, City Park, the Joe Brown park in New Orleans East, and the Lakefront, as well as the city’s recreation facilities, each are competing for the public support and funding, while each feel compelled to address “balance” between activities individually, rather than as a whole.

Audubon leaders sought in 2014 to pass an early renewal of two property taxes that will expire in 2021 and 2022, but the ballot measure was rejected with support from only 35 percent of voters. Several panelists said that because the relationship between the various park agencies is so complicated, voters do are losing faith that their tax money will go to actual parks.

“Audubon Institute is not a park; it’s a large organization that runs a park,” said Mike Moffitt, a former commissioner of City Park. “It seems to me very confusing to have funding so broadly distributed, because it doesn’t get any focus. If the city needs to fund insectariums and aquariums and other projects, then they should fund them, but they shouldn’t fund them thinking they’re funding a park.”

The need for funding drives initiatives for park leaders to create “amusements” that charge admission, the panelists said, but every new amusement takes away from land that was previously open to the public, a concept described as “We pave our parks in order to save them.” Debra Howell of Save Audubon Park said that these projects often end up losing money anyway, and become part of the larger system that needs financial support, rather than contributing to it.

“Every new facility loses money rather than raises money, and the next thing you hear is yet another plan for a new facility,” Howell said. “At some point when does it become obvious that none of these new facilities are going to raise money?”

Justin Kray of “City Park for Everyone” noted that City Park is also likely to begin looking for tax support from voters, and that he too thinks a single citywide system would be a better approach. He noted that while individual parks such as Audubon and City Park have conducted surveys of their users, he’s not aware of any survey of recreation of the entire city.

“We’re continuing to perpetuate bad solutions to a problem that’s structural about how parks are funded,” Kray said. “I’d like to contemplate a future where we have a unified parks governance and operational strategy citywide. All these things are related, and the health of the city is in large part related to the health of the parks system.”

As City Park looks for tax funding and the expiration date for those two Audubon taxes draw near, Howell said, the city should instead rededicate the Audubon money to the creation of some sort of unified park system.

“That is an opportunity,” Howell said. “There’s no reason Audubon should get a new tax or a new millage, but 2021-22 could be the opportunity to look at a citywide park millage.”

Scott Howard of Parks for All said his opposition to the Audubon tax in 2014 was not because he did not support Audubon, but because he too wanted to see that money more equitably distributed across the city. The system is not broken — people enjoy the parks — but the general public does not understand how decisions are made about them.

“We do have a system that could be vastly improved by reconsidering the organization of our parks for efficiency and also for transparency. At the basic level, Joe Citizen doesn’t know who runs each park,” Howard said. “By being fractured and being opaque, I think it creates a collective distrust of parks. … It’s like a dark hole. Where’s the money going to go? What’s it going to be for?”

Howard is also on the board of the New Orleans Recreation Department, and he said he is proud of what that entity has accomplished for organized sports. But the disconnect between it and the numerous parks is what drives the individual parks to try to provide organized sports, Howard said, and it could be resolved by a more centralized effort.

“I think the key has more to do with our fractured system,” Howard said. “I believe we have the potential for a lot of overlap providing these services.”

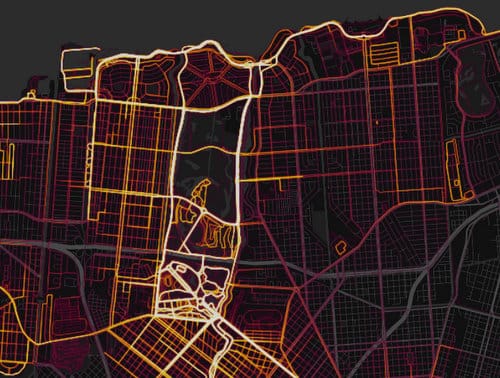

The Strava heatmap also shows high intensity of use of City Park, the lakefront and Bayou St. John. (via Strava.com)

The focus on the largest parks has a tendency to leave other areas of the city out. Moderator Keith Hardie noted that a map of the city shows that residents of New Orleans East and Algiers actually have far less access to parks near their homes than the rest of the city, for example.

“We had playgrounds uptown and we had playgrounds in Carrollton, but when they designed New Orleans East, I don’t know if they put those parks in,” Hardie said.

Likewise, Monte Shallett of the Lake Area Advisory Council says he has been fighting against development of the parks along the lakefront, which he said are protected by state law. He called the lakefront parks a “string of pearls,” and said the lakefront could become a much more popular recreation destination if it had a publicly-developed master plan.

“If it was generated as a master plan, I think it would have traction, and I think it would be sellable to City Council,” Shallett said.

Robert Thompson of City Beautiful, an organization that conducts the development and maintenance of small neighborhood “pocket parks” around the city, suggested that a centralized system might not have to be a single city department, but instead some sort of consistent set of rules that govern all the parks together.

“We don’t have to have a Department of Parks under Mayor Landrieu. We just need a set of rules,” Thompson said. “There are ways, without creating a commission or department, to govern our community response to recreational needs and prevent the possibility of a rogue commission going off and destroying our parks.”

Howard said that there is time to work out the details of how exactly a unified system would work, but there are also models around the country to study.

“We need to educate ourselves about this and build trust in one another and in our city administrators and park administrators,” Howard said. “If and when we do create a big millage that affects the whole city, we can be confident we’re doing the right thing.”

Excellent coverage of this issue! Thank you, Uptown Messenger. We all need green space!